HISTORY

Galileo Galilei: Architect of Modern Astronomy

Written By: Mustafa Syed Ahmed

Jan 18th, 2023

Childhood

Along the winding paths of scientific history, few names resonate as profoundly as Galileo Galilei, the Renaissance polymath whose insatiable curiosity and groundbreaking observations forever altered our understanding of the cosmos. Born in Pisa on February 15, 1564, Galileo emerged as a beacon of intellectual enlightenment during a time when dogma and tradition often stifled the pursuit of knowledge. His revolutionary contributions to astronomy, physics, and the scientific method have left an indelible mark on the scientific landscape, cementing his status as the "father of modern science."

Galileo's childhood house (Photo Credit: Heritage History)

Born to parents Vincenzo Galilei and Giulia Ammannati in the year 1564, Galileo enjoyed an above-average lifestyle in the city of Pisa, and later Florence, throughout his formative years. Both his parents came from bourgeois households, and even though he didn’t live in exorbitant luxury like much of the nobility of the time, as his father’s profession of musical composing and lute playing wasn’t very well paying, he still belonged to a reasonably privileged and well-to-do family.

Galileo’s father’s idea for his future and Galileo’s own ideas for his future constantly conflicted. Though his father wanted Galileo to become a doctor, Galileo never seemed to be very passionate about the profession; almost joining a monastery instead. Later on in life, when his father sent him to the University of Pisa to get a medical degree, he ignored his father’s wishes, instead gaining an interest in mathematics and philosophy. After much convincing, Galileo finally got his father’s permission to pursue his newfound interests.

After University

In 1585, departing from his pursuit of a medical degree, Galileo embarked on a transformative journey into the realm of mathematics. Embracing his passion, he delved into teaching, a decision that not only altered his career path but set the stage for groundbreaking contributions to the world of science. The year 1586 marked a pivotal moment in Galileo's burgeoning academic career. While instructing at a school in Siena, he authored and published his inaugural book, a scholarly work detailing Archimedes' methodology for determining the relative densities of substances using a balance. This publication served as the inaugural step in his quest to disseminate scientific knowledge and cemented his burgeoning reputation as a scholar of great promise.

Galileo's return to his alma mater, the University of Pisa, in 1589 ushered in a period of intellectual exploration and innovation. Though his series of essays from this period remained unpublished, their contents harbored significant breakthroughs. Notably, these writings expounded on the concept of testing theories concerning bodies in descent by employing an inclined plane—a notion that would later form the bedrock of his pioneering work in physics and mechanics. Tragedy struck in 1591 with the passing of his father, Vincenzo Galilei. Suddenly burdened with the responsibility of providing for his two younger sisters, Galileo found himself propelled towards seeking greater financial stability. This quest for stability culminated in his appointment as a professor of mathematics at the prestigious University of Padua. This position not only elevated his standing in the academic sphere but also laid the groundwork for his future monumental discoveries and contributions to scientific thought. Galileo met the mother of his future children, Maria Gamba, during his years at Padua. They had a daughter, Virginia, in 1600, followed by another daughter, Livia, in 1601, and finally a son, Vincenzo, in 1606.

The Telescope

In 1609, Galileo encountered reports of a revolutionary optical instrument in Venice. This marvel, a telescope, held the potential to magnify distant objects, bridging immense spatial gaps and bringing them seemingly closer to the viewer. Fueled by an insatiable curiosity and leveraging his expertise as a physician, Galileo embarked on a quest to craft his version of this instrument with unmatched precision. Months of tireless experimentation and precise calibration led to Galileo's monumental creation: a telescope boasting a magnification capability eight to nine times greater than its Venetian precursor. With a focal length of approximately 1.5 meters and an aperture of around 3 centimeters, his telescope provided unparalleled clarity and vision, allowing for unprecedented observations of celestial bodies. Recognizing the astronomical potential of his invention, Galileo strategically maneuvered to secure the rights, entering into an agreement with the Venetian Senate. This groundbreaking telescope quickly gained acclaim among merchants and navigators, who eagerly employed it in maritime voyages to chart unexplored territories and navigate the seas with greater precision.

An illustration from the 19th century captures Galileo presenting his telescope to the Venetian senators. (Photo Credit: ThinkStock)

However, Galileo's intent diverged from terrestrial explorations. Redirecting his gaze skyward, he turned his meticulously crafted instrument toward the heavens, pioneering a new era of astronomical discovery. Through the lens of his powerful telescope, Galileo revealed an unseen celestial landscape, challenging established perceptions. His meticulous observations shattered the prevailing belief in the moon's immaculate perfection. The lunar surface, once envisioned as a pristine, unblemished sphere, was unveiled in all its rugged glory, punctuated by towering mountains and scarred by deep craters. But Galileo's revelations extended far beyond the moon. His unyielding scrutiny revealed the celestial ballet around Jupiter. He observed, meticulously noting the positions of celestial bodies, the orbits, and the changing configurations of Jupiter's moons—later known as the Galilean moons: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Compiling his groundbreaking observations and revelations, Galileo immortalized his discoveries in the seminal treatise "Sidereus Nuncius" (Starry Messenger).

Two of Galileo's first telescopes; in the Museo Galileo, Florence. (Photo Credit: Britannica)

The Fall

Galileo's beliefs about what comets are were not aligned with the Jesuit opinion on the nature of comets at the time, and over a period of disputes over this, the Jesuits began to see Galileo as an opponent. In 1616, Galileo wrote a letter to the Grand Duchess Christina of Lorraine, arguing that there should be a non-literal interpretation of religious text in scientific matters as literal interpretation would go against what has already been proved by science. This letter was badly received by the church.

“To our natural and human reason, I say that these terms ‘large,’ ‘small,’ ‘immense,’ ‘minute,’ etc. are not absolute but relative; the same thing in comparison with various others may be called at one time ‘immense’ and at another ‘imperceptible.”

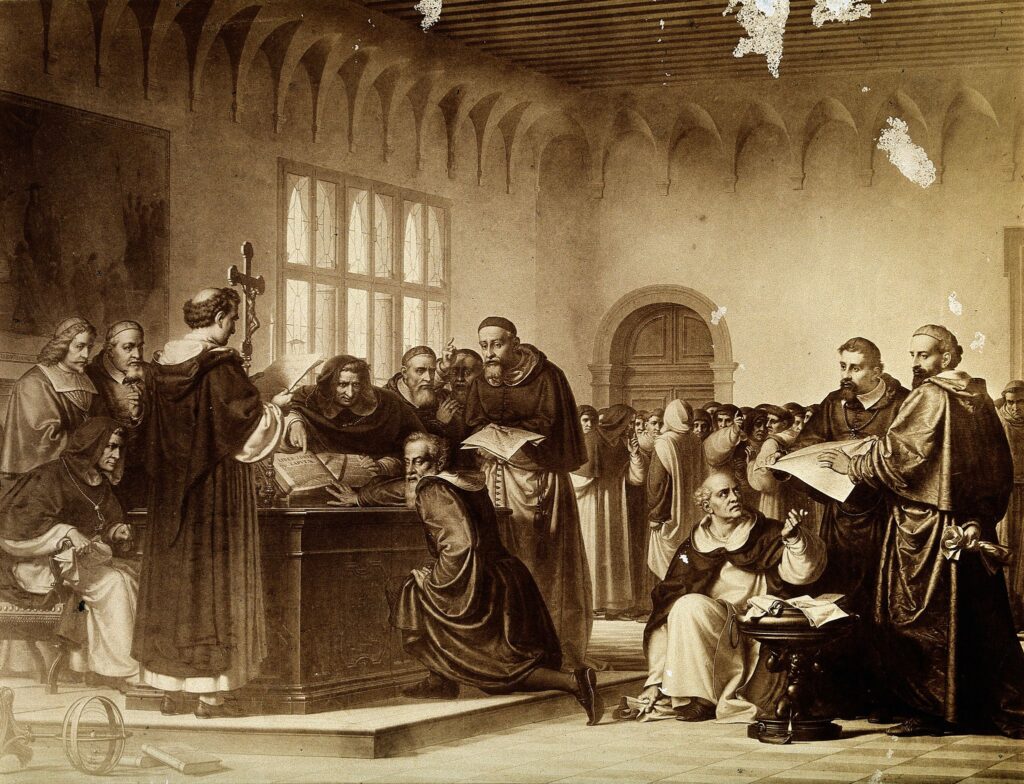

In 1632, Galileo published "Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief Systems of the World - Ptolemaic and Copernican," which once again argued that the religious interpretation of space and its workings were wrong. The book was quickly banned by religious parties. In 1633, he was accused of heresy and put on trial. Galileo was sentenced to life imprisonment, though this was somewhat softened to become a house arrest instead.

Galileo faces the Inquisition, standing trial for charges of heresy. (Photo Credit: Wellcome Collection)

In 1634, tragedy struck again, as his daughter Virginia passed away. Galileo, who was a sickly old man at this point, was completely destroyed by this development; however, he did not let it defeat him. He began work on his final book, "Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Concerning the Two New Sciences." Using the essays he did not publish back in 1590 during his time at the University of Pisa as a base, his book reached the famous conclusion that the distance that a body moves from rest under uniform acceleration is proportional to the square of the time taken. As Galileo’s work could not be published in Italy anymore, it had to be smuggled to Holland where it got published instead. At the age of 77, Galileo Galilei passed away in early 1942. The church would only accept fault in the situation 350 years later when the pope at the time acknowledged that errors had been made in the case of Galileo, though not admitting that the church was wrong in charging Galileo with heresy.

Conclusion

Galileo's legacy extends far beyond the realm of astronomy. His insistence on empirical evidence and the scientific method paved the way for future scientific inquiry. The laws of motion, inertia, and gravitational acceleration, later expounded by Sir Isaac Newton, owe a debt to Galileo's pioneering work in physics. His research ideologies are the purest representation of the scientific method. Likewise, his unyielding persistence towards discovery and innovation is an exemplary benchmark that all aspiring scientists should strive towards. For Galileo to challenge the preconceived notions and beliefs of his time in spite of the constraints placed upon him is a testament to the enduring power of curiosity that has propelled humanity to a greater understanding of the earth and beyond. In essence, it is essential for one to remember that no matter the obstacles in your path, the spirit of inquiry triumphs in the end. We humans can only achieve so much in the limited timespan of our lives, but our ideals are immortal and adhering to them no matter the opposition is our legacy. In the words of the great Galileo himself,

"E pur si muove" – and yet, it moves.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

Receive amazing space news and stories that are hot off the press and ready to be read by thousands of people all around the world.