EXPLORE

animals that were sent to space

- Published On

August 15th, 2024

- Author

Hamza Majid

Have you ever watched those whimsical cartoons where animals are casually strolling on the moon or zooming between planets in colorful spaceships? You might recall classic moments like Bugs Bunny’s cosmic antics in Haredevil Hare or the zany moon chase between Tom and Jerry. These playful scenes, while delightful, echo a real-life fascination with space that dates back far beyond animation. Before humans ventured into the cosmos, a group of brave animals blazed the trail, embarking on historic space missions that paved the way for human spaceflight. In this article, we’ll dive into the reasons behind sending animals into space, their crucial roles in early scientific testing, and the extraordinary stories of these pioneering creatures from around the globe.

Understanding Biological Effects

Space presents extreme conditions like microgravity, radiation, and isolation. Animals help scientists understand these effects on biological systems. The knowledge gained from these experiments is crucial in designing countermeasures to protect human astronauts from the potential hazards of long-term space travel. For instance, microgravity can cause muscle atrophy and bone density loss, which have been studied extensively using animal models.

Before risking human lives, it was crucial to ensure that space travel was safe. Animals were sent to test the limits of spacecraft systems and life-support mechanisms. These tests included evaluating the performance of the spacecraft, the efficacy of life-support systems, and the overall survivability of living organisms in space. By doing so, scientists could identify and rectify potential issues, thereby increasing the safety of subsequent manned missions.

Insights gained from these missions have informed medical knowledge, particularly in areas such as cardiovascular health, muscle atrophy, and bone density loss. For example, the study of cardiovascular changes in animals has helped scientists understand how the human heart might respond to extended periods in microgravity. Similarly, research on the skeletal systems of animals has provided valuable data on preventing and treating bone density loss in astronauts. Animals have long been used in scientific testing to advance human knowledge and safety. In medical research, animals have helped in developing vaccines, surgical techniques, and understanding disease processes. This section will provide a brief overview of the roles animals have played in various scientific fields.

Laika

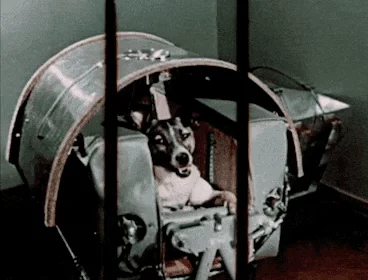

Video showing Laika in the Sputnik Capsule where her cabin was pressurized and equipped with an air regeneration system that provided oxygen, food, and water in gelatinized form. (Credit: NASA)

Laika, a stray mongrel from the streets of Moscow, became a historic figure as the first animal to orbit the Earth. Launched aboard Sputnik 2 on November 3, 1957, she was part of a Soviet mission aimed at demonstrating the feasibility of space travel for living creatures. The mission followed the success of Sputnik 1, and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev pushed for a new spectacle to showcase Soviet space prowess. To meet the November deadline, engineers rapidly designed and built Sputnik 2, incorporating a basic life-support system with an oxygen generator, a fan to regulate temperature, and devices to manage carbon dioxide levels.

The spacecraft was equipped with sensors to monitor Laika's vital signs, including heart rate, respiration rate, and blood pressure. During the launch, Laika experienced extreme stress, with her heart rate soaring from 103 to 240 beats per minute at peak acceleration. After reaching orbit, however, the spacecraft's thermal control system malfunctioned due to issues with the "Block A" core. This led to a dangerous rise in cabin temperature to 40 °C (104 °F). Despite early telemetry indicating that Laika was eating her food and adapting to weightlessness, the excessive heat and stress eventually led to her death. Communication with Sputnik 2 was lost after a few hours, and Laika died of overheating on the fourth orbit.

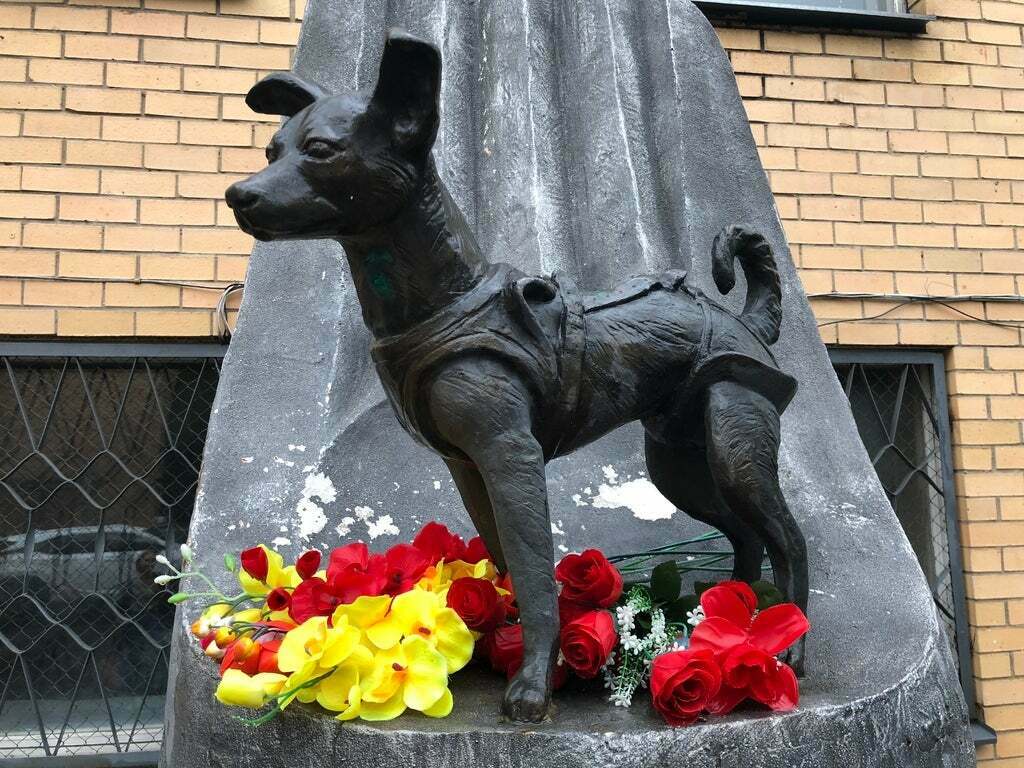

The (surprisingly small) monument that now stands near a military research station is shaped like an abstract rocket that morphs into a hand, cradling Laika towards the stars. (Photo Credit: Cults 3D)

The mission was crucial for advancing human space exploration, as it provided some of the earliest data on how living organisms respond to the conditions of space. Scientists were eager to understand the effects of spaceflight on biological systems, making Laika's mission a necessary precursor to human space travel. Although her survival was never anticipated, the experiment aimed to prove that a living organism could endure the rigors of orbit, providing valuable insights into the impacts of weakened gravity and increased radiation. Laika's death sparked significant ethical debate, with conflicting reports about the exact cause and time of her demise. It was not until 2002 that the true circumstances of her death—overheating due to a malfunctioning thermal control system—were revealed. Despite the controversy, Laika's legacy is honored by monuments and memorials, including a statue unveiled in 2008 near the military research facility in Moscow, and she remains a poignant symbol of the sacrifices made in the pursuit of space exploration.

Ham The Chimpanzee

Ham, a chimpanzee, was part of the Mercury-Redstone 2 mission (part of the U.S. space program's Project Mercury) that launched from Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico on January 31, 1961. How did he become part of this program? He was bought from a rare bird farm in Florida after being captured by animal trappers. Beginning in July 1959, Ham was trained at Holloman Air Force Base for about 219 hours over a 15-month period. During this training, he was required to perform tasks in response to electric sounds and lights. Of course, in these drills, he was rewarded with the stereotypical banana pellet. As a chimpanzee with similarities to humans, Ham was considered the perfect candidate to help scientists understand the link between humans and space travel. Equipped with physiological sensors to monitor his vitals, he was launched into space for 16 minutes and 39 seconds, eventually splashing down in the Atlantic Ocean. His capsule, which was damaged and sank deeper than expected, was recovered by the USS Donner. This landing led to him being renamed from No. 65 to Ham, as officials wanted to avoid the bad press that would come from the death of a "named" chimpanzee if the mission had failed.

After a 16-minute flight, which included six and a half minutes of weightlessness, Ham splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean and was promptly retrieved by the U.S.S. Donner. The ship's captain greeted him warmly as he came aboard. (Photo Credit: NASA)

After his return, the post-flight examination revealed several issues with his physical health, including a loss of 5.3% of body weight, dehydration, and a small abrasion on the bridge of his nose. Despite these challenges, Ham’s contributions proved invaluable. Following his historic flight, he lived for many years at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., and later joined a small group of chimps at a zoo in North Carolina. Ham died in 1983 at the age of 25 and was laid to rest at the International Space Hall of Fame in New Mexico, where a monument honors his significant contributions to space exploration.

Félicette

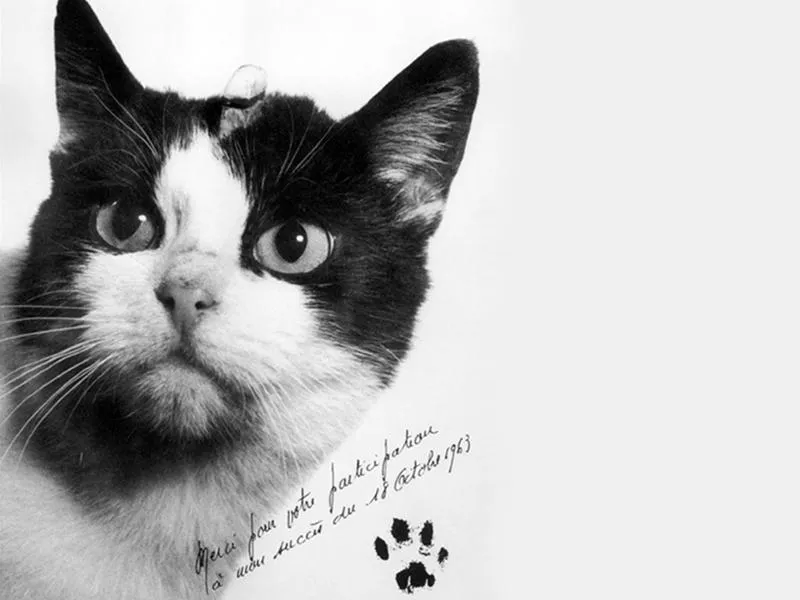

Félicette, a French cat obtained from a "pet dealer" along with 13 other cats, was sent into space on October 18, 1963, from the Interarmy Special Vehicles Test Centre aboard the Veronique Rocket. The rocket reached an altitude of 154 km after about 5 minutes, with the goal of studying the effects of space travel on neurological activity. Previously known as C341 by the Centre d’Enseignement et de Recherches de Médecine Aéronautique (CERMA), she was later named Félicette. The reason for assigning numbers instead of names was to prevent scientists from becoming attached to the animals. Her mission was part of a series of experiments conducted by the French government to study the effects of microgravity on living organisms. To monitor her health and collect valuable data, Félicette was fitted with electrodes and kept in small containers for long periods as part of her 'astronaut training.'

The text reads "Thank you for your participation in my success of 18 October 1963" and in 2020, a team unveiled a bronze statue honoring the feline. (Photo Credit: Smithsonian Magazine)

Félicette’s mission was successful, providing valuable data on the effects of space travel on the brain. Electrodes implanted in her brain transmitted neural impulses back to Earth, offering insights into how the brain responds to spaceflight conditions. However, the story did not have a happy ending; Félicette was humanely euthanized a few months after her mission for further study, though it was later admitted that nothing useful was learned from the autopsy. In 2019, a crowdfunding campaign raised funds to erect a statue in her honor at the International Space University in Strasbourg, France.

Fruit Flies

Fruit flies, chosen for their genetic similarity to humans, were the first animals to venture into space. In 1947, these tiny pioneers were launched 109 kilometers into the atmosphere at the span of 190 seconds aboard a V-2 rocket. This groundbreaking experiment was designed to investigate how high-altitude radiation exposure might affect living organisms. By studying the impact of space radiation on these flies, scientists aimed to gain insights into potential genetic changes and assess the risks that space radiation could pose to future astronauts. The experiment was a crucial step in understanding the broader implications of space travel on biological systems.

Upon their successful return, the fruit flies were parachuted down to New Mexico, where they were recovered for further analysis. In February 1953, several unmanned balloons were launched, carrying fruit flies as test subjects. Although most of the flies died or were lost, twelve survived a flight on February 26, 1953. Three years later, in February 1956, a similar experiment sent mice, guinea pigs, a fungus sample, and fruit flies to an altitude of 115,000 feet, with all animals successfully recovered alive. By July 1958, the United States Navy advanced these experiments by launching a manned high-altitude balloon carrying Malcolm David Ross, Morton Lee Lewis, and fruit flies to 82,000 feet, marking the first time a flight reached the stratosphere. In this flight, the balloon's cabin mimicked sea-level pressurized conditions, offering new insights into the effects of such environments on living organisms.

On February 20 1947 a V-2 loaded with fruit flies traveled 67 miles, the point where space officially begins. Therefore, those bugs are considered the first animals to ever visit the final frontier. (Photo Credit: How Stuff Works)

By 1968, scientists discovered that fruit fly larvae exposed to both radiation and space flight had a higher rate of premature death, accelerated aging, and genetic mutations compared to flies exposed to either condition alone. Another study from the same year revealed that pre-flight radiation combined with space travel caused significant damage to the sperm of the fruit flies, a result not observed in flies exposed to just one of these conditions. These findings highlighted the complex and potentially harmful effects of space travel on living organisms, informing future space missions and biological research.

Tortoises

Two tortoises were sent around the Moon on the week-long Zond 5 mission on September 14, 1968, to study the effects of long-duration space travel on living organisms. The mission aimed to gather data in preparation for human lunar missions and is described by NASA as “the first successful circumlunar mission carried out by any nation.”

The tortoises, along with other biological specimens, were among the first Earth organisms to travel to the Moon and back. They survived the mission, landing in the Indian Ocean via parachute, and were taken back to Moscow on October 7th, where they were later dissected to study the effects of space travel on their bodies. The results showed that their physical changes were due to a lack of food rather than space travel, with the primary effect being a 10% loss of body fat.

Albert I and II

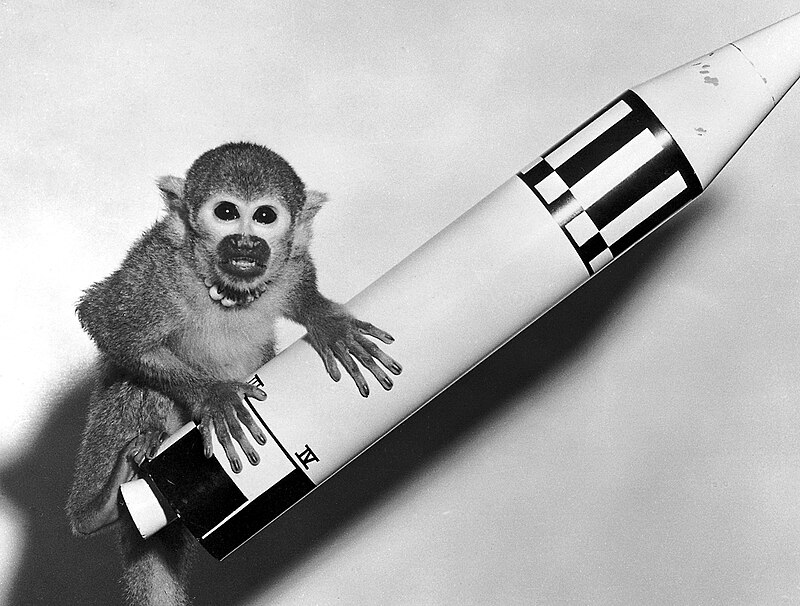

Albert II was a male rhesus macaque monkey who became the first primate and the first mammal to travel to outer space. On June 14, 1949, he soared from Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico, USA, reaching an altitude of 83 miles (134 km) aboard a U.S. V-2 sounding rocket. (Photo Credit: The Yak Mag)

Albert I and II, rhesus monkeys, were part of early U.S. efforts to study the effects of space travel on primates. Albert I was launched in June 1948, and Albert II followed in June 1949. Albert I's mission ended in failure due to a technical malfunction that caused him to suffocate within his cramped capsule before the rocket ever launched into space. To prevent this from happening again, the capsule was redesigned between flights to enlarge the cramped space. Albert II, however, did reach space, achieving a height of 134 km.

Although he successfully reached space, he died upon re-entry due to a parachute failure. These early missions highlighted the challenges of space travel and the need for improved safety measures. Both Albert I and II perished during their missions, serving as early martyrs in the quest for space exploration. Their sacrifices underscored the importance of rigorous testing and safety protocols.

Gordo

Gordo, a squirrel monkey also known as Old Reliable, was launched from Cape Canaveral on December 13, 1958, aboard a US PGM-19 Jupiter rocket to test the effects of space travel on small primates. The rocket reached a height of 500 kilometers before descending back to Earth and landing in the South Atlantic. Gordo, however, did not survive the return due to a parachute failure, and his body, along with the vessel, was never recovered. Despite this, scientists were able to monitor his health and take readings that would later help their cause, thanks to Gordo's space suit, which was fitted with instruments such as a thermometer and a microphone. His contributions helped improve safety measures for subsequent missions and aided in the development of safer spacecraft and re-entry procedures.

Baker and Able

In 1959, space pioneer Miss Baker, a squirrel monkey, made history by traveling to space aboard a Jupiter IRBM rocket. This remarkable journey, with a scale model of the rocket showcased here, marked a significant milestone in the early era of space exploration. (Photo Credit: Wikipedia)

Baker, a squirrel monkey, and Able, a rhesus monkey, were launched from Florida aboard a Jupiter rocket on May 28, 1959. Their mission aimed to test the effects of space travel on primates and gather data for future manned missions. During their launch, the rocket reached an altitude of 480 kilometers before safely returning to Earth, where it was later recovered from the Caribbean by the USS Kiowa, a fleet tug that served the US Navy from 1943 to 1972. One of the reasons this mission was successful was the precautions taken before the flight, as all six consecutive Alberts had previously died due to spaceflight hazards. Among these precautions were testing the capsules about four weeks before the flight and fitting them with monitors to constantly collect data.

Able died a few days after the mission due to an infection at one of his three electrode sites, which could not be treated through surgery. In contrast, Baker lived for many years afterward, reaching the age of 27. She became a popular figure and lived at the U.S. Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama, until her death in 1984.

Belka And Strelka

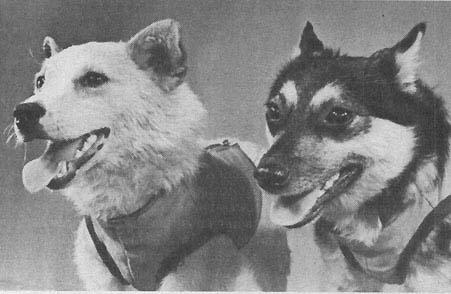

Belka and Strelka, two Russian dogs, were launched aboard Sputnik 5 on August 19, 1960. Their mission marked a significant milestone in space exploration as they spent 27 hours in orbit, completing 17 revolutions around Earth before returning safely. This achievement made them the first dogs to travel to space and return alive. The mission's success was pivotal in demonstrating that living organisms could endure the harsh conditions of space travel and re-entry, thereby paving the way for human spaceflight and setting the stage for Yuri Gagarin’s historic orbit of Earth in 1961.

1960: Belka and Strelka, a couple of stray mutts impressed into the Soviet space program, become the first living creatures to return alive from an orbital flight. (Photo Credit: Wired)

After their historic flight, Belka and Strelka lived out their lives in the Soviet Union. Strelka's offspring were famously given to U.S. President John F. Kennedy and his family as a gesture of goodwill. Kennedy affectionately referred to them as "pupniks," a playful nod to their spacefaring heritage. This gesture underscored the role of these pioneering dogs in international diplomacy and highlighted the collaborative spirit of the space race era. Belka and Strelka's legacy endures as a testament to the early efforts in space exploration and the international cooperation that followed.

Pchyolka and Mushka

Soviet dogs Pchyolka and Mushka spent a day in orbit on December 1, 1960 on board Korabl-Sputnik-3 (Sputnik 6). (Photo Credit: Reddit)

Pchyolka, a Soviet space dog, was launched on a mission aboard Sputnik 6 on December 1, 1960. The spacecraft carried a variety of biological specimens, including other animals, insects, and plants, with the objective of studying the effects of space travel on living organisms. Unfortunately, the mission ended in failure. A reentry error occurred when the retrorockets failed to deactivate as planned. As a result, the spacecraft was intentionally set to self-destruct to prevent foreign powers from inspecting the capsule and its contents upon its return to Earth. This drastic measure was taken to protect the sensitive data and technology within the spacecraft.

Mushka, another dog initially slated to participate in the mission, was not sent into space. Although she underwent rigorous ground-based tests, she was ultimately removed from the mission. The decision was made because Mushka refused to eat properly during her preparation, a crucial issue that could have jeopardized the success of the mission. Her dietary refusal raised concerns about her health and readiness, leading to her replacement by another candidate better suited for the demanding conditions of space travel.

Veterok and Ugolyok

Veterok and Ugolyok were two of over 100 mongrels selected for the experiment. The primary criteria were very specific. Dogs were picked up from the streets because mongrels were considered hardier and smarter than thoroughbreds. (Photo Credit: Russia Beyond)

Veterok and Ugolyok were launched aboard Cosmos 110 on February 22, 1966, where they spent a record-breaking 22 days in orbit before landing back on March 16. Both dogs were safely returned to Earth and studied for the effects of their prolonged stay in space. The immediate effects observed included signs of cardiovascular deconditioning, dehydration, muscle loss, coordination issues, and weight loss, which took weeks to recover from. Fortunately, there were no long-term health problems.

This spaceflight’s duration was not surpassed by humans until Soyuz 11 (the only crewed mission to board the world's first space station, Salyut 1) in June 1971 and remains the longest spaceflight for dogs. Their contributions remain significant in the history of space exploration.

Wrapping Up

The animals sent to space played an indispensable role in the early days of space exploration. Their sacrifices have not been forgotten, as they laid the groundwork for human spaceflight, contributing to our understanding of the final frontier. As we look to the stars and plan for future missions to Mars and beyond, we remember these pioneering creatures and their contributions to humanity's quest for knowledge.

These brave animals, from Laika to Félicette, exemplify the spirit of exploration and the relentless pursuit of discovery that drives us to explore the cosmos. Their stories remind us of the importance of courage, sacrifice, and the unwavering desire to push the boundaries of what is possible. Who knows? Maybe you and your dog could be the next to venture into space, continuing the legacy of these extraordinary pioneers and contributing to the next chapter in human space exploration.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

Receive amazing space news and stories that are hot off the press and ready to be read by thousands of people all around the world.