HISTORY

The Story of William Herschel

History

The Story Of William Herschel

10 Min Read

Wonder is one of the oldest and greatest ideals of the human mind, and the night sky is the oldest and greatest beacon of wonder for men since the dawn of life. In every millennium and century of our existence, countless human beings have looked towards the firmament and the many stars that loom ever radiant in its primordial confines. Chief among those who have peered into the heavens and found new truths in their great immensity is William Herschel, whose discovery of Uranus and his pioneering work in mapping the Milky Way significantly altered our understanding of the universe’s cosmology. In this article we will examine his life and the principles behind his work that enabled his myriad contributions to the world of astronomy, as well as how those principles continue to shape and give meaning to the burgeoning saga of human advancement.

Early Life

Frederick William Herschel, later known simply as William Herschel, was born on November 15, 1738, in Hanover, a city in present-day Germany. His father, Isaac Herschel, a regimental musician in the Hanoverian Guards, played an influential role in fostering the early musical education of William and his siblings. Despite the modest circumstances of the Herschel family, young William demonstrated remarkable talent in both music and mathematics. This unique combination of creativity and analytical thinking became a defining characteristic of his later scientific endeavors.

Herschel’s formative years unfolded against the backdrop of the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), a conflict that severely disrupted his family’s financial stability. At the age of 14, he joined the Hanoverian Guards as an oboist, following in his father’s footsteps. However, the difficult wartime conditions, coupled with limited prospects in Hanover, compelled him to seek a better future. In 1757, at the age of 19, Herschel emigrated to England.

Once in England, Herschel initially pursued a career in music, quickly establishing himself as a teacher, composer, and performer. He secured a position as the organist at Halifax Parish Church and later moved to Bath, where he became a prominent figure in the thriving musical scene. There, he organized concerts, composed symphonies, and performed at prestigious events, earning widespread recognition. This phase of his life not only provided financial stability but also cultivated the discipline and creative structure that would later underpin his groundbreaking work in astronomy.

This is the historic Observatory House in Slough, located on the corner of Windsor Road, now known as Herschel Street. It was the residence William Herschel moved into after his time in Bath and where he lived for the rest of his life. He passed away on 25 August 1822 and is laid to rest at St Laurence’s Church nearby. (Photo Credit: Royal Astronomical Society)

Herschel’s transition from musician to astronomer began in the 1770s, driven by an insatiable curiosity about the universe and a fascination with the scientific discoveries of the time. He immersed himself in studying astronomical and mathematical texts, drawing inspiration from the works of luminaries such as Isaac Newton and Galileo Galilei. His passion for stargazing led him to begin observing the night sky through commercially available telescopes. Dissatisfied with their optical limitations, Herschel resolved to build his own instruments.

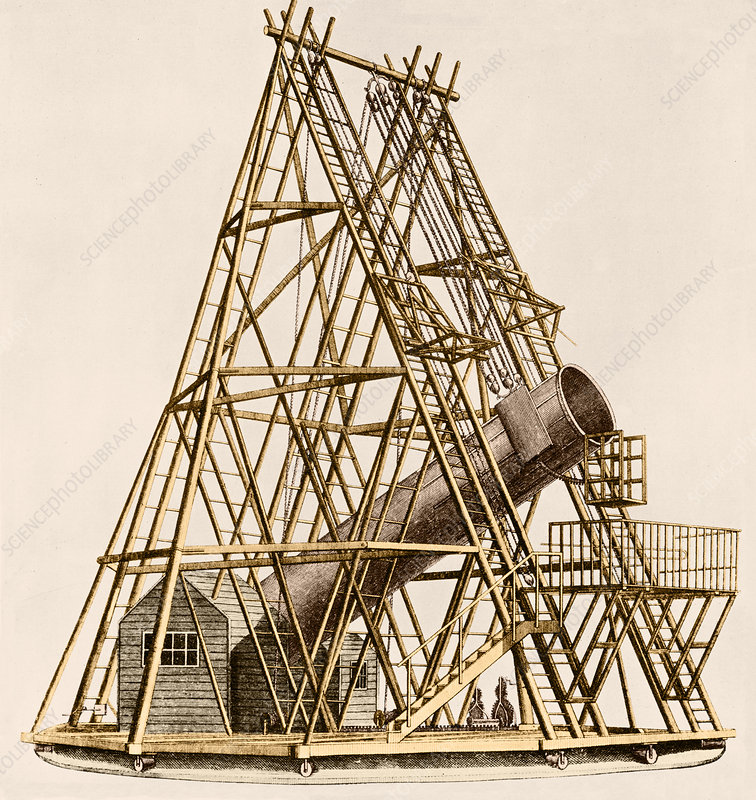

Teaching himself the intricate art of grinding and polishing mirrors, Herschel embarked on an ambitious project to construct telescopes of unparalleled quality and power. His dedication and ingenuity yielded remarkable results. Over the years, he constructed increasingly sophisticated telescopes, culminating in the creation of a 40-foot reflector telescope with a 48-inch diameter mirror—the largest and most advanced telescope of its time. This engineering marvel allowed Herschel to observe celestial objects with unprecedented clarity, revolutionizing the field of observational astronomy and paving the way for numerous discoveries.

Discovery of Uranus and Astronomical Fame

On March 13, 1781, William Herschel made a discovery that would forever link his name to the history of science. While systematically scanning the night sky from his home in Bath, he identified a celestial object that he initially thought was a comet. However, further observation revealed that the object was orbiting the Sun, and subsequent calculations by other astronomers confirmed that Herschel had discovered a new planet—Uranus. This monumental discovery marked the first time in recorded history that a planet beyond Saturn had been identified, expanding the known boundaries of the solar system and challenging the prevailing understanding of the cosmos.

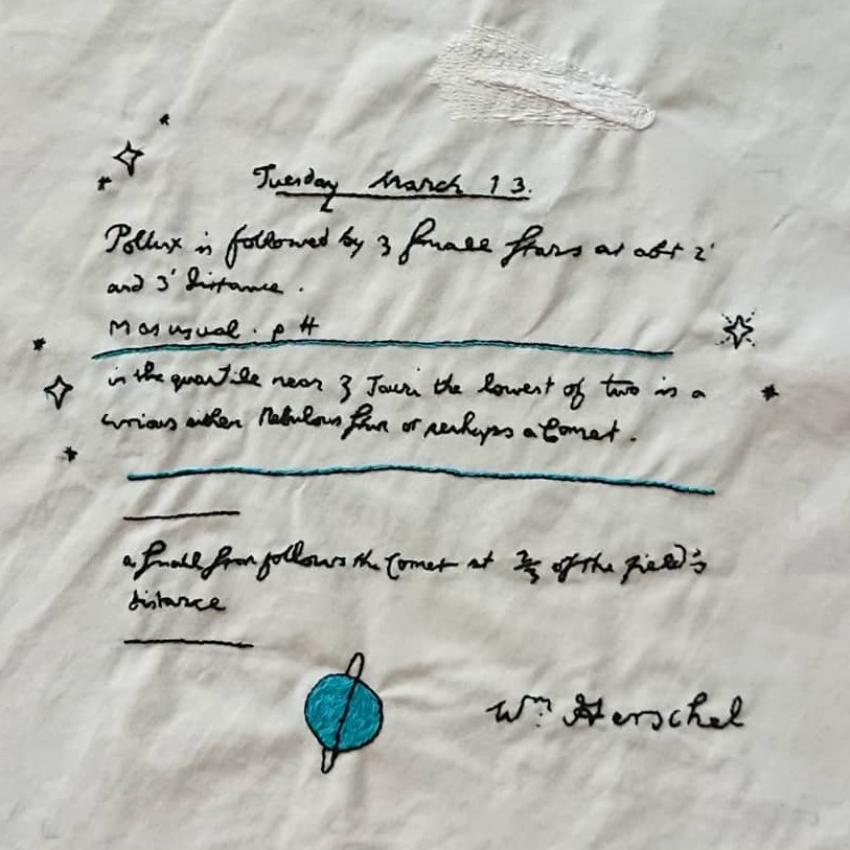

A section of William Herschel's manuscript from the night of his monumental discovery of Uranus in 1781. The handwritten text details his observations: "Tuesday, March 13. Pollux is followed by three small stars at about 2' and 3' distance. M as usual. p H. In the quartile near (symbol) Tauri, the lowest of the two is a curious object—either a nebulous star or perhaps a comet. A small star follows the comet at two-thirds of the field's distance." (Photo Credit: Royal Astronomical Society)

Herschel initially proposed naming the planet "Georgium Sidus" (George's Star) in honor of King George III, reflecting his gratitude toward the monarch. While the name gained some acceptance in England, it was eventually replaced by "Uranus," following the classical tradition of naming planets after mythological figures. Uranus, named after the Greek god of the sky, symbolized humanity’s expanding knowledge of the heavens and established a precedent for future discoveries.

In recognition of his groundbreaking achievement, King George III awarded Herschel a royal pension of £200, enabling him to conclude his musical career and dedicate himself entirely to astronomy. He was also knighted and appointed as the King’s Astronomer, a prestigious role that marked the beginning of a transformative phase in his life. Additionally, the Royal Society honored him with the Copley Medal in 1781, underscoring the significance of his discovery and his contributions to science.

Cataloging the Stars and Nebulae

William Herschel's contributions to astronomy went far beyond the discovery of Uranus. After being elected to the Royal Society, he received Charles Messier's Catalog of Nebulae and Star Clusters, which inspired him to examine and expand upon its entries. On October 23, 1783, he began a systematic survey of the night sky, using a stationary telescope to scan east-west bands each night and eventually covering the entire visible sky from Great Britain. Over two decades, Herschel recorded 2,500 new nebulae and star clusters in his General Catalogue of Nebulae. This catalog later became the foundation of the New General Catalogue (NGC), and of the 7,840 objects it contains today, 4,630 were discovered by Herschel and his son, John.

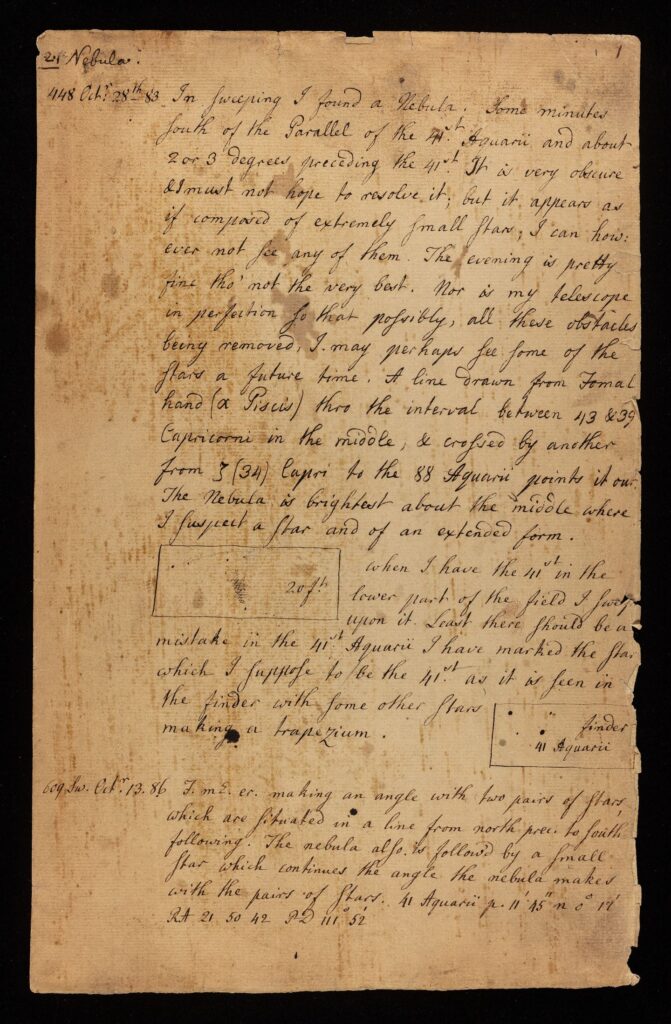

A glimpse of his list's of nebulae and star clusters, in order of discovery, with observational descriptions and some drawings. (Photo Credit: The Royal Observatory)

Herschel's groundbreaking observations revealed that many nebulae were not mere clouds of gas but vast collections of stars, leading him to hypothesize the existence of galaxies beyond the Milky Way. He also pioneered the study of stellar motion, demonstrating that stars, including the Sun, move through space. To further his work, Herschel constructed powerful telescopes, including a 40-foot-long instrument, the largest of its time, although he relied more on a smaller, 20-foot telescope for practical use. These innovations and discoveries laid the foundation for modern astronomy, revolutionizing humanity's understanding of the cosmos.

Infrared Radiation

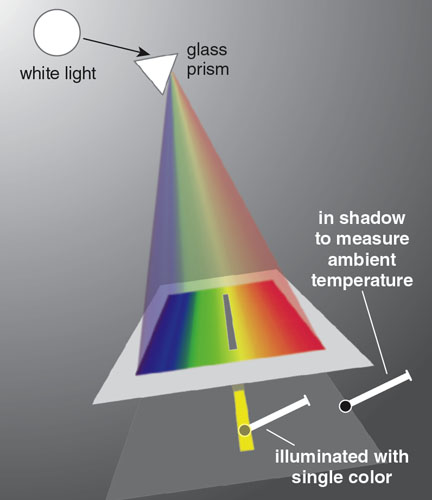

In addition to his groundbreaking contributions to astronomy, Sir William Herschel made a historic advancement in physics in 1800 with the discovery of infrared radiation. This revelation stemmed from his interest in understanding how sunlight’s heat interacted with colored filters used in solar observation. Herschel had noted that different colored filters seemed to pass varying amounts of heat, leading him to hypothesize that the colors themselves might have distinct temperatures. To test his theory, Herschel devised an innovative experiment, using a prism to disperse sunlight into its component spectrum of colors: violet, blue, green, yellow, orange, and red.

To measure the temperature within each color, Herschel employed three thermometers with blackened bulbs to maximize heat absorption. He placed one thermometer within a specific visible color while using the other two, situated outside the spectrum, as control samples. His meticulous measurements revealed that all visible colors showed temperatures higher than the controls, with the temperatures steadily increasing from the violet to the red portion of the spectrum. This pattern prompted Herschel to extend his investigation beyond the visible red portion, into a region of the spectrum where no light was visible to the naked eye.

A diagram depicting William Herschel's groundbreaking experiment where he directed dispersed colors from a prism onto a piece of cardboard with a slit, allowing only a single color to pass through. To measure the relative heating effect of different colors, he placed one thermometer in the light beam and another in the shadow, leading to the discovery of infrared radiation. (Photo Credit: American Scientist)

To his amazement, the area just beyond the red portion of the spectrum exhibited the highest temperature of all, indicating the presence of invisible radiation. Herschel named these rays “calorific rays” (from the Latin word for heat) and conducted further experiments to study their properties. He discovered that these rays, now known as infrared radiation, behaved like visible light—they could be reflected, refracted, absorbed, and transmitted.

Herschel’s experiment was revolutionary because it was the first time someone demonstrated the existence of light outside the visible spectrum. By proving that there are types of light that human eyes cannot detect, Herschel opened the door to a deeper understanding of the electromagnetic spectrum. His discovery laid the groundwork for future advancements in fields as diverse as astrophysics, thermodynamics, and infrared technology, profoundly shaping our understanding of light and energy.

Collaboration with Caroline Herschel

Central to Frederick William Herschel’s astronomical achievements was his collaboration with his sister, Caroline Herschel. Born in Hanover, Germany, Caroline overcame significant obstacles, including disfigurement from childhood smallpox and family pressures to conform to traditional gender roles, to become one of the most accomplished astronomers of her era. Initially joining her brother in England as a housekeeper and assistant after he established himself as a musician, Caroline quickly demonstrated her intellectual capabilities and began contributing meaningfully to his work.

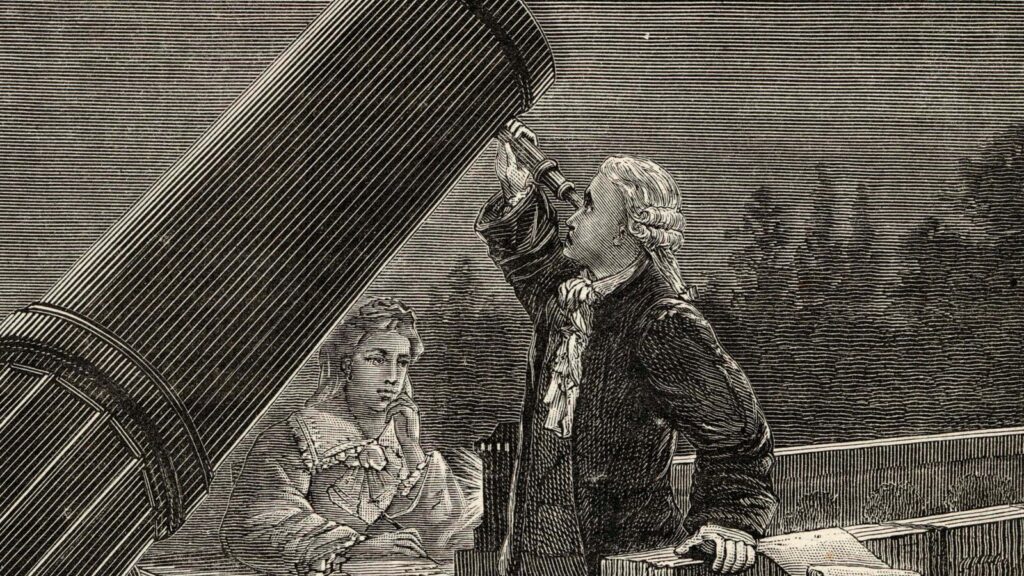

A detailed depiction of Caroline Herschel assisting her brother William during the historic night of March 13, 1781, when he discovered the planet Uranus. (Photo Credit: Royal Irish Academy)

Caroline’s early role primarily involved recording William’s observations, organizing extensive notes, and calculating orbital parameters of celestial bodies. However, her skills and ambitions soon extended far beyond clerical tasks. As William delved deeper into observational astronomy, Caroline took on the technical challenges of polishing mirrors, maintaining telescopes, and managing the demanding schedule of nighttime observations. Working under physically exhausting and often extreme weather conditions, the siblings forged a partnership that produced groundbreaking astronomical discoveries.

Caroline Herschel was not merely an assistant. Her independent contributions to astronomy were significant. Between 1786 and 1797, she discovered eight comets, including the periodic comet 35P/Herschel–Rigollet, which retains her name in modern catalogs. She was the first woman to receive a Gold Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society in 1828 and was later made an Honorary Member of both the Royal Astronomical Society (1835) and the Royal Irish Academy. In addition to her comet discoveries, she cataloged a series of nebulae and star clusters, some of which William used in his sweeping studies of deep space objects. This shared work culminated in the creation of the "New General Catalogue", a cornerstone reference for astronomers.

Challenges and Personal Life

William Herschel’s path to scientific prominence was not without significant personal and professional challenges. Constructing and maintaining his colossal telescopes—at the time the most advanced optical instruments in the world—required immense financial resources, physical labor, and technical skill. Herschel's experiments with mirror grinding and polishing consumed years of trial and error, often conducted in uncomfortable and physically demanding conditions. These instruments, which included his iconic 40-foot telescope completed in 1789, expanded the range of human vision deeper into the universe but imposed exacting demands on his health and finances.

A color enhanced illustration the 50 cm telescope that resulted in his appointment as private astronomer to King George III of England. (Photo Credit: Science Photo Library)

Beyond his professional endeavors, Herschel was deeply committed to his family. In 1788, at the height of his fame following his discovery of Uranus, he married Mary Pitt, a wealthy widow with a young daughter, Ann. The couple’s only child, John Herschel, inherited his father’s passion for science and became one of the 19th century’s leading polymaths, making significant contributions to astronomy, photography, and mathematics. William’s family played a stabilizing and supportive role in his life, particularly during his periods of intense work and innovation.

Despite his scientific achievements, William Herschel grappled with the realities of advancing age and declining health. In his later years, he retreated to a quieter life in Slough, England, but continued his observations and theoretical inquiries. His perseverance exemplified a lifelong commitment to discovery, culminating in his death on August 25, 1822, at the age of 83.

Legacy and Influence

The legacy of Frederick William Herschel extends beyond the discovery of Uranus, an achievement that fundamentally altered the understanding of the solar system by extending its known boundaries for the first time since antiquity. His meticulous star surveys revealed the structure of the Milky Way galaxy, and his cataloging of nebulae laid the groundwork for modern galactic astronomy. Herschel was among the first to propose the existence of stellar evolution, hypothesizing that stars and nebulae might be connected through long cosmic processes.

One of Herschel's most enduring contributions was his pioneering work on infrared radiation. In 1800, while exploring the thermal properties of sunlight with prisms, he discovered invisible heat rays beyond the red end of the visible spectrum. This finding expanded the scope of light study beyond visible wavelengths, profoundly influencing fields like astrophysics, optics, and chemistry. The telescopes Herschel built were marvels of engineering and influenced astronomical instrument design for generations. His 40-foot reflector telescope remained the largest operating telescope in the world for half a century, inspiring the development of larger and more precise observatories. In 2009, the European Space Agency launched the Herschel Space Observatory, named in his honor, which observed the universe in infrared and continued his tradition of pushing the boundaries of human vision.

Conclusion

The story of William and Caroline Herschel is a testament to the unyielding human spirit that strives to uncover the secrets of existence, even amidst adversity and pervasive ignorance. Their partnership, built on mutual respect and shared ambition, transcended societal constraints and emphasised the sheer impact of intellectual cooperation in the chronicle of human progress. From the shimmering discovery of distant worlds to the invisible warmth of infrared light, the Herschels revealed that even in the depths of abyssal darkness, there is light waiting to be uncovered. In their legacy, we are reminded of Carl Sagan’s poignant words:

“Somewhere, something incredible is waiting to be known.”

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

Receive amazing space news and stories that are hot off the press and ready to be read by thousands of people all around the world.