HISTORY

The Early Life, Work, and Death of Nicholas Copernicus

- Published On

March 20th, 2024

- Author

Ayaan Atif

Imagine a scene straight out of a historical drama: it's a crisp winter morning in Toruń, Poland, circa 1473. The air is tinged with frost, and the cobbled streets bustle with the energy of daily life in this vibrant northern city. It is within this atmospheric backdrop that a remarkable event unfolds - the birth of Nicolaus Copernicus, a luminary whose name would one day be etched into the annals of scientific history. His dad, Nicolaus, was a wealthy dealer, and his mom, Barbara Watzenrode, likewise came from a main trader family. Nicolaus was the most youthful of four youngsters. After his dad's passing, between 1483 and 1485, his mom's sibling Lucas Watzenrode (1447-1512) took his nephew under his security. Watzenrode, a potential priest in Varmia, oversaw young Nicolaus' education and prepared him for his future role as a church canon. Between 1491 and around 1494 Copernicus concentrated on human sciences, including cosmology and soothsaying at the College of Cracow. In the same way as other understudies of his time, he left prior to finishing his certification, continuing his examinations in Italy at the College of Bologna, where his uncle had gotten a doctorate in standard regulation in 1473. The Bologna time frame (1496-1500) was short yet critical.

Early Life

For a period Copernicus resided in a similar house as the main cosmologist at the college, Domenico Maria (1454-1504). Novara had the obligation of giving yearly visionary expectations for the city, gauges that incorporated every single gathering however focused on the destiny of the Italian rulers and their adversaries. Copernicus, as is known from Rheticus, "aide and witness" to a portion of Novara's perceptions, and his contribution with the development of the yearly gauges implies that he was personally acquainted with the act of soothsaying. Novara likewise presumably acquainted Copernicus with two significant books that outlined his future tricky as an understudy of the sky: Epitoma in Almagestum Ptolemaei ("Encapsulation of Ptolemy's Almagest") by Johann Müller (1436-1476) and Disputationes adversus astrologianm divinatricenm ("Controversies against Divinatory Crystal gazing") by Giovanni Picodella Mirandola (1463-1494).

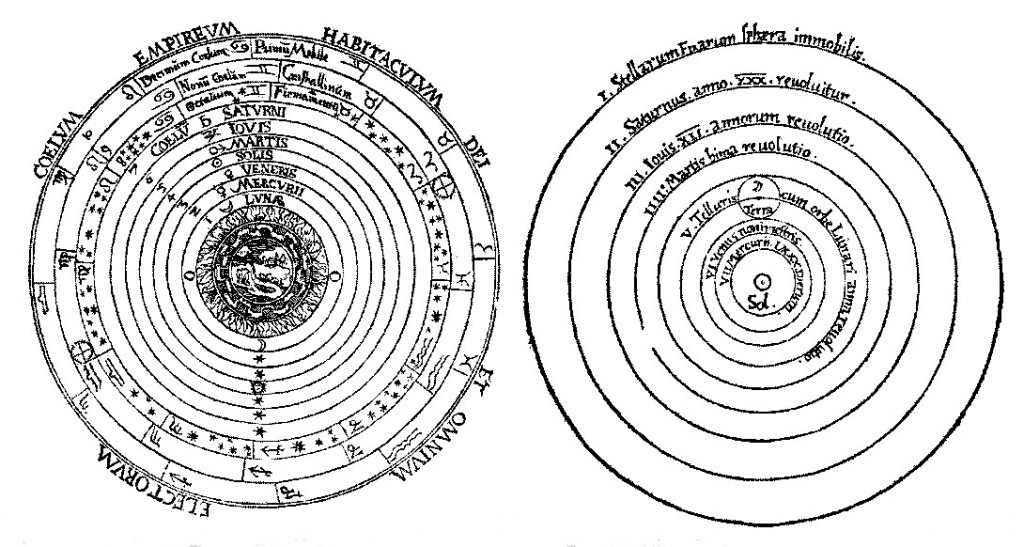

The main gave a rundown of the underpinnings of Ptolemy's cosmology, with redresses by Johann Müller and basic developments of specific significant planetary models that could have been interesting to Copernicus of headings prompting the heliocentric speculation. Pico's Controversies offered a staggering distrustful assault on the groundworks of crystal gazing that resonated into the seventeenth hundred years. Among Pico's reactions was the charge that, since cosmologists differ about the request for the planets, crystal gazers couldn't be sure about the qualities of the powers given from the planets.

His Work

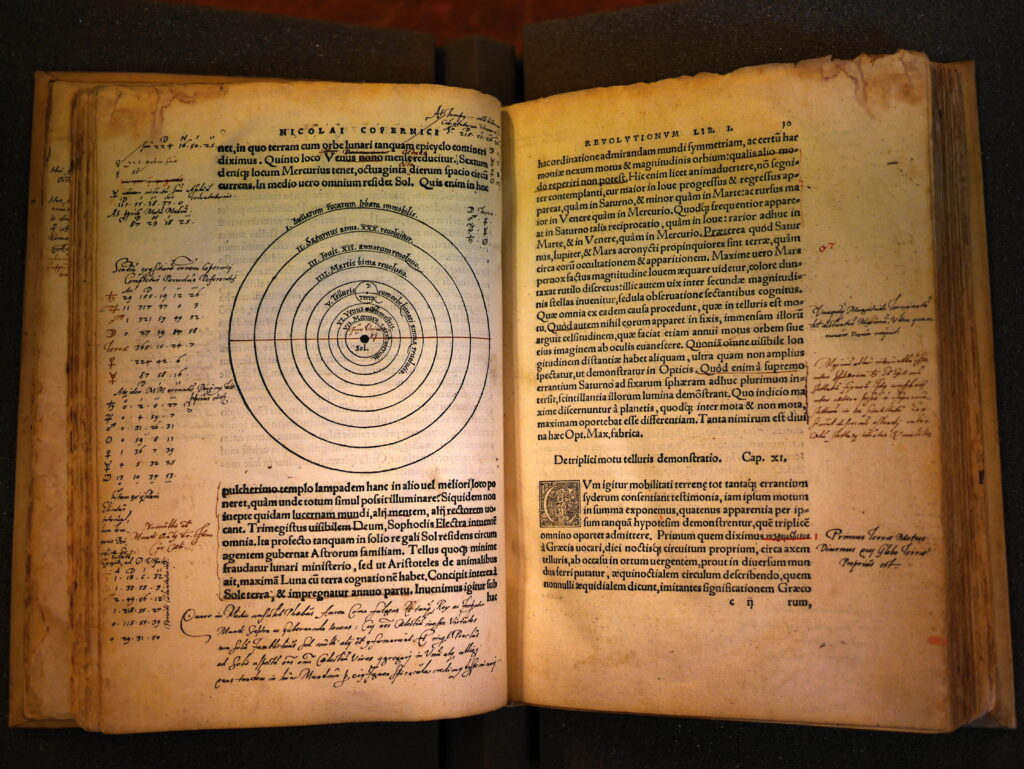

Through detailed mathematical calculations and observational data, he presents a compelling argument for the heliocentric model, supported by his insights into planetary motion and celestial mechanics. (Photo Credit:Wikimedia Commons)

Just 27 recorded perceptions are known for as long as Copernicus can remember (he without a doubt made more than that), the majority of them concerning shrouds, arrangements, and conjunctions of planets and stars. The primary such realization happened on Walk 9, 1497, at Bologna. In "De revolutionibus, book 4, part 27, Copernicus revealed that he had seen the Moon obscure "the most brilliant star in the eye of the Bull," Alpha Tauri (Aldebaran). When he distributed this perception in 1543, he had made it the premise of a hypothetical case: that it affirmed the very size of the clear lunar measurement. However, in 1497 he was most likely involving it to help with checking the new-and full-moon tables obtained from the usually utilized Alfonsine Tables and utilized in Novara's gauge for the year 1498.

In 1500 Copernicus talked before an intrigued crowd with regards to Rome on numerical subjects, yet the specific substance of his talks is obscure. In 1501 he remained momentarily in Frauenburg however before long got back to Italy to proceed with his examinations, this time at the College of Padua, where he sought after clinical investigations somewhere in the range of 1501 and 1503. At this ann Müller and basic extensions of specific significant planetary models that could have been interesting to Copernicus of bearings prompting the heliocentric speculation. Giovanni's Questions offered a staggering suspicious assault on the underpinnings of crystal gazing that resounded into the seventeenth hundred years. Among Giovanni's reactions was the charge that, since stargazers differ about the request for the planets, celestial prophets couldn't be sure about the qualities of the powers given from the planets.

De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium

In 1514, Copernicus dispersed a manually written book to his companions that set out his perspective on the universe. In it, he recommended that the focal point of the universe was not Earth, however that the sun lay close to it. He additionally recommended that World's pivot represented the ascent and setting of the sun, the development of the stars, and that the pattern of seasons was brought about by Earth's insurgencies around it. At long last, he suggested that World's movement through space caused the retrograde movement of the planets across the night sky (planets once in a while move in similar bearings as stars, gradually across the sky from one night to another, yet at times they move in the inverse, or retrograde, course). Copernicus completed the principal original copy of his book, "De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium" ("On the Transformations of the Eminent Circles") in 1532. In it, Copernicus laid out that the planets circled the sun as opposed to the Earth. He spread out his model of the planetary group and the way of the planets. He didn't distribute the book, be that as it may, until 1543, only two months before he kicked the bucket. He strategically devoted the book to Pope Paul III.

A comparison of the geocentric and heliocentric models of the universe unveils a fascinating contrast between two divergent views of cosmic order. (Photo Credit: history.ucsb.edu)

Controversy Regarding Publication

Its publication, however, is the epitome of ancient controversy. Wait let me explain. By August 29th, "De revolutionibus orbium coelestium" was prepared for printing. Rheticus brought the manuscript back to Wittenberg and entrusted it to the printer Johann Petreius in Nürnberg, a prominent printing center with Petreius being the top printer there. However, as Petreius couldn't oversee the printing process, he enlisted Andreas Osiander, a Lutheran theologian experienced in printing mathematical texts, for the job.

Osiander took an unconventional step by writing a letter to the reader, which he inserted instead of Copernicus's original Preface after the title page. In this letter, he suggested that the content of the book wasn't meant to represent truth but rather provided a simpler method for calculating celestial positions. The letter was unsigned, and Osiander's authorship was only disclosed by Kepler fifty years later. Osiander also subtly altered the title to make it seem less assertive of reality.Opinions on Osiander's actions vary. Some, like Rheticus at the time, were appalled by what they saw as a massive deception. Others argue that it was only because of Osiander's intervention that Copernicus's work was read and not immediately dismissed.

Conclusion

Copernicus passed on from a cerebral drain on May 24, 1543 (age 70). His works before long made discussion in European logical and strict circles by testing numerous convictions that had become strict doctrine since the conclusion of the Traditional Age 1,000 years prior. Let us end with a saying by Nicholas Copernicus himself:

“To know that we know what we know, and to know that we do not know what we do not know, that is true knowledge”

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

Receive amazing space news and stories that are hot off the press and ready to be read by thousands of people all around the world.